[Events recap] Re-envisioning STEM Education and Workforce Development for the 21st Century12/11/2021

Introduction The Journal of Science Policy & Governance (JSPG) and Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society launched a call for papers and competition focused on Re-envisioning STEM Education and Workforce Development for the 21st Century. The call for papers and competition for op-eds and policy position papers will result in a Special Topics Issue of JSPG to be released in 2022 that will comprise the most compelling papers. Read the call for submissions. As part of this partnership, JSPG and Sigma Xi hosted a series of educational webinars led by experts from Advancing Research Impact in Society (ARIS), New America, and the Association of American Universities (AAU) to examine policy changes in STEM education and workforce development, and a policy writing workshop for op-eds and policy position papers to help prospective authors improve their submissions to the special issue. View the event recordings. In addition, as part of the JSPG Leadership Chat Series, our staff interviewed a number of established leaders in science policy at multiple career stages within JSPG, who discussed relevant and timely issues in the field as related to topics published in the journal. This includes JSPG governing board members and JSPG advisors. Many of these speakers have deep knowledge on the topics included in this call for papers, including DEI in Science Policy (Mehrdad Hariri); Shaping the Future of Science Policy (Tobin Smith) and Shaping the Future of Education and Workforce Development (Shalin Jyotishi). The writing workshop provided writing instruction (Deborah Stine) emphasized the importance of science policy training for the next generation of leaders in science policy, which was emphasized in the chat on the topic of Professional Development for Graduate Students and Postdocs (Lida Beninson). Below are summaries of the webinar series, written from the perspective of an early career participant (graduate student, postdoc levels), and a brief summary of the writing workshop. We integrated these chats into the respective summary, as relevant for that particular event leading up to the call for papers.

What drew you to attend? During the COVID-19 pandemic, the world witnessed the scientific process unfold in real time and broadcast through mainstream media. The demand for immediate results did not allow adequate time for scientific replication and further casted doubts about promising findings of new studies. For the general population, it is difficult to sift through numerous new information, and it can also be particularly challenging when knowledge about the scientific process is limited. I was inspired to promote K-12 STEM education so that young people adopt knowledge about the scientific process early on, enabling them to discern quality science upon reading new information. This important skill can be applied in the STEM workforce, through mentorship, and for developing good policies. Upon hearing about the expert panelists speaking on strategies for delivering quality STEM education to K-12 students, I was excited to learn what is currently being done by STEM professionals. The panel was moderated by Thomas Tubon and highlighted three experts in bridging the pathway from K-12 to the STEM workforce. Takeaways from speakers Natalie Kuldell developed a STEM educational program, originally supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), and sustained the program by starting a non-profit organization that creates teaching labs for educators and students. Natalie noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has unveiled gaps and pitfalls of social systems, resulting in teachers and schools stepping in to fulfill the needs of students, especially for K-12 students from marginalized and underrepresented backgrounds. It is difficult to ask schools to have patience and to invest time with students until they have mastery in skill sets given how many responsibilities have fallen on K-12 schools. There cannot be a one size fits all solution to K-12 education due to a variety of needs across many different communities. There needs to be a connection between the quality of educational resources and empowerment of teachers. With extensive expertise in STEM curriculum design and program evaluation, Teshell Ponteen Greene brings national attention to outreach and access to innovative and advanced STEM education for racially and ethnically diverse K-12 students. Teshell suggested partnering with large organizations and companies, which have already established outreach programs, in order to tap into a talent pool of young underrepresented learners. This will connect K-12 students with local industry employers and organizations. To diversify STEM talent in K-12 education, colleges must provide pathways for teachers earning education degrees with internship opportunities to work in multiple STEM labs. Lastly, educators can build and strengthen alliances by creating opportunities for students from various backgrounds to work together, even internationally, diversifying teamwork in STEM fields. Linnea Fletcher spearheads initiatives to bring industrial biotechnology and cell therapy lessons into classrooms by assisting teachers in adapting to virtual teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. With support from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Linnea developed a strategy to increase access to biotechnology in K-12 STEM education. Linnea believes that all education should be authentic by having students use applied science, technology, engineering, and math. An example of effective education is having middle school students create products that elementary school students can use. Another point Linnea added was that students working in the industry should get credit for learning new skill sets and translate this knowledge into credits towards their college degree. Industry partnerships are also necessary to deliver applied STEM in schools, and this creates a stream of skills building and opportunities to enter into the STEM workforce after graduation. Overall takeaways To solve a complex problem in STEM education, it requires creative solutions with a robust team of STEM professionals partnering with educators and industry partners. Diversifying science teamwork in education and expanding collaborations locally, nationally, and internationally would strategically create pathways from K-12 to the STEM workforce. Access to quality STEM education for students of all backgrounds benefits society as a whole and can lead to its betterment. Policymakers can re-evaluate lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic in regards to maximizing virtual education, expanding quality Internet access to rural communities, and providing equitable resources to low income communities. The goal is to relieve the added strain placed on teachers and schools so that they can fulfill their mastery of educating and mentoring students to be future STEM leaders and professionals. The webinar pairs nicely with Mehrdad Hariri’s JSPG leadership fireside chat focused on DEI in science policy. Mehrdad discussed when he first entered into policy work at the turn of the new millenia, science and policy were separate. Therefore, he took on leadership roles bridging science and policy and paving the way for emerging scientists. Through regular attendance at the AAAS annual meeting and inspired by what he learned, Mehrdad encouraged early career scientists to connect with other science policy experts by attending AAAS events and to engage with them in learning how to be a changemaker, which also applies to students and young people from all backgrounds.

What drew you to attend? As the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the transition of students into 4-year colleges and graduate programs, calls were made to bring classes online, shift to pass/no pass grading, and waive admissions tests as application requirements. Nearly two years later, postsecondary institutions are deciding which education policies to phase out or continue. When I learned about this webinar, I was curious to learn how 3 different institutions were ensuring a successful STEM experience for students and equipping graduates for the careers they would enter into. Toby Smith moderated this conversation, featuring leaders from a liberal arts college, a technical public college, and a private school focused on biomedical graduate programs. Takeaways from speakers Susan Singer shared that the pandemic highlighted the importance of the residential college community as an equalizer, providing all students with access to broadband and communication software. Susan also mentioned SAT/ACT test waivers as a way to increase access to education for undergraduate students, and noted that liberal arts institutions who engage in holistic admissions successfully incorporate multiple factors into admission decisions. Noting that STEM skills can offer benefits even for non-STEM majors, Susan mentioned that incorporating research into general education requirements could be a way to increase access to these skills. This pathway enables all students to develop critical thinking, written communication, and research presentation skills, resulting in postsecondary graduates who are well-prepared for the careers of their choice. Alongside coursework, mentorship was highlighted as a key force in guiding students to “go to college on purpose” so that they may relate their coursework and extracurricular activities to employers as part of their career story about the grand societal challenge they see themselves contributing to. For example, a history major might complete a data science minor in order to enhance their work in an art gallery. Institutions can curate the optimal portfolio of courses through quarterly conversations with industry, a strategy Susan mentioned that 2-year colleges use to build what is needed to ensure well-equipped graduates. With a focus on retention, Kaye Husbands Fealing illuminated options to resolve the “last mile” problem of college completion for enrolled students by reinforcing their sense of belonging and ensuring secured funding for tuition. With these measures in place, students can experience a greater sense of well-being, resulting in the ability to focus on their schoolwork. This work includes the sophisticated technical content that STEM is known for. One challenge in completing this work is accessing support. Kaye underscored the importance of creating culture shifts that facilitate advancement, retention, and graduation by removing this barrier. A key driver of this culture shift is reducing the stigma associated with asking for help, so that the high expectations and rigor are met with a welcoming environment to access support. With this support, students will be set up for success in the gatekeeper courses and beyond. And as students become alumni and engage in the future of work, they may expect to encounter careers where they spend 10 years in one area, then switch to another area of science or even a new industry. In conversations with alumni from Georgia Tech, Kaye heard positive feedback on developing flexible skill sets including non-technical skills like writing, leadership, communication, and history. With an eye toward a robust lifelong learning process, where new skills could be added 20+ years post-graduation, colleges can look over the horizon and anticipate the professional education they might offer for those looking to refresh skills in their current area or train in preparation for a career pivot. Cynthia Fuhrmann suggested that moving to online platforms has enhanced opportunities for students to complete graduate school milestones and diversify their career development options. Virtual qualifying exams, dissertation defenses, and committee meetings have been easier to schedule and are now recognized for being as viable as in-person sessions for these activities. Due to reduced registration costs and elimination of travel fees, graduate students and postdocs can explore more career options. While in the past it may have only been possible to attend conferences where they were presenting scientific work, they are now able to get more out of their conference budgets and attend virtual professional society conferences to learn more about industries they may choose to join. With the apprenticeship model of the PhD strongly focused on being an academic scientist at a time where more PhD graduates are finding roles outside of the academy, Cynthia shared that being more deliberate in how students gain transferable skills like communication and team-oriented work is vital to the future of graduate STEM education. She referred to an NSF report that emphasized the importance of a student-centered pedagogy, where the needs of students inform the design of the program. Programs aligned with the needs of students entering careers outside of the academy produce scientists who communicate with empathy and are able to work interculturally, demonstrating leadership skills in any industry they enter. Overall takeaways The pandemic has heightened awareness of how access to post secondary STEM training can be broadened. From holistic admissions and inclusive retention strategies that promote well-being, through career exploration, launch, and reskilling, institutions offering 4-year colleges and graduate degrees can improve access for students from all backgrounds along the continuum by focusing on the needs of the students they serve. Undergraduate programs can ensure that STEM and non-STEM students receive a balanced education with complementary skills outside their areas of focus. Graduate programs can consider revisiting and revising the graduate model of apprenticeship to support students obtaining roles outside of academia. With these changes in place, graduates will complete their programs as lifelong learners who can translate their expertise to new industries and acquire new skills throughout their career journey as the landscape shifts. Whether another pandemic is on the horizon or not, students at these levels will be prepared for the road ahead. This webinar dovetails with Toby Smith’s JSPG leadership chat focused on how early career scientists can be involved in shaping the future of science policy. Toby shared his experiences as a legislative assistant at MIT’s Washington Office, where he translated the work of scientists to policymakers and found that students were the most effective advocates for continued funding of scientific research. For early career scientists, he emphasized the importance of getting involved with organizations like AAAS to learn how science policy works, learning how to talk to non-scientists about the importance of science for the public, and in allocating time during graduate training to developing a robust set of professional skills applicable to careers outside of academic research. If you listen to Toby’s remarks during the chat, you will also hear highlights about the origins of the peer review process as the mechanism for determining what science should be funded, and equity-focused alternatives that have been proposed. Career, Technical, and Community College Education for a Robust STEM Workforce Webinar community college Chat with Shalin Jyotishi

What drew you to attend?

In some higher education circles, the importance of career, technical education, and community colleges is not sufficiently addressed. Meanwhile, community colleges make up approximately one third of the undergraduate student population in the US, are lower cost and thus more accessible to students compared to 4 year institutions, are more diverse than their 4 year institution peers, and are important centers for continuing education and professional development. JSPG's choice to intentionally emphasize the importance of community colleges and career and technical training centers to the equitable and accessible development of the STEM workforce drew me to attend this webinar moderated by Shalin Jyotishi, a Senior Analyst in Education and Labor at New America and JSPG’s Senior Advisor. The webinar featured speakers from the federal government, private industry, and importantly community colleges themselves. Takeaways from speakers Van Ton-Quilivan shared her former experience as the Executive Vice Chancellor of California Community Colleges, the largest system of higher education in the USA, where she successfully established workforce development as a state priority and recruited expanded public investments in the system. In addition, she shared insights into the workforce demands of the allied healthcare industry with workers who are often trained at community colleges, via certifications, and in the industry itself. She made a convincing argument for the role of community colleges as affordable, accessible, and inclusive destinations for developing competencies for the middle skill STEM technicians, which do not require a 4-year degree, while also serving as a stepping stone into 4 year institutions for students planning to obtain advanced degrees. With over 1200 community colleges in the US, the community college infrastructure already exists to solve workforce development and upskilling challenges at scale in an inclusive and efficient manner. Amy Kardel offered insights from an information technology perspective, fueled by her wide experience in the sector with Comptia- the computer trade industry association- and as a tech entrepreneur. She identified the importance of retaining diverse talent in STEM, highlighting the leaky pipeline problem which the technology sector faces. She also discussed certifications as a “ticket into tech” which verify worker competencies and can be completed anywhere, including in the US or internationally, in high schools, or community colleges. Working to assist manufacturing companies grow as part of the National Institutes of Standards and Technology (NIST)’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP), Mary Ann Pacelli offered perspectives on the importance of the manufacturing industry in the US. She highlighted that the sector has over 12 million jobs with average earnings between $28-29/hour, but faces a critical challenge of employee recruitment and retention amid the changes brought about by automation. This is exactly where community colleges come into play, as they offer opportunities for short term skill development programs. In addition, she advocated for more young scholars to be exposed to and to consider careers in manufacturing. Overall takeaways The webinar made apparent the need for continued collaboration between industry, community colleges, career and technical education, and other degree granting four year institutions. Young scholars should be exposed to and encouraged to consider STEM careers which are accessible to them via short term training programs, certifications, or associate degrees at community colleges. Data documenting the program outcomes and the employment and earnings of community college program completers may help with student awareness and uptake. Additionally, the existing community college infrastructure in the US is uniquely positioned to support short term upskilling and non-degree credentials. Finally, as Van Ton-Quinlivan implored us, education and workforce development must seek to “follow the siren call” of what employers need while, as Amy Kardel highlighted, intentionally working to retain talent in STEM. The webinar pairs nicely with Shalin Jyotishi’s JSPG leadership fireside chat focused on shaping education and workforce development. There, Shalin emphasized new models for career preparation of middle skilled workers, reduced use of proxies for skills amid better verifiable records of student learning and competencies, and expanded demand for quality jobs which offer a living wage, benefits, and scheduling predictability. Listen in to the chat for his hopeful message for how the new technologies and the next generation of the US workforce will demand more from both their education and their work. Writing workshop Writing workshop Chat with Lida Beninson In addition to the webinar series, the policy writing workshop was meant to equip students, policy fellows, and early career researchers with the skills needed to write effective, innovative and actionable op-eds and policy position papers on STEM education and workforce development. JSPG governing board member Deborah Stine provided instruction on elements needed to construct op-eds and policy position papers, followed by opportunities to practice outlines for writing proposals in breakout rooms. The workshop pairs nicely with Lida Beninson’s JSPG leadership fireside chat focused on professional development for graduate students and postdocs. There, Lida emphasized reforms needed to support the next generation of scientists and the value which input from early career researchers brings to these reforms. She also discussed university barriers to change, and how early career researchers themselves can take action towards reforms in graduate education through particular organizations and scientific societies. Conclusion Early career perspectives expressed in this post reveal the topics that the next generation considers important in STEM education and workforce development, and ways in which they can shape the future of policymaking in this area. Submit your ideas to this issue of JSPG by January 23, 2022! Post compiled and edited by Adriana Bankston. Introduction On November 12, 2021, the Journal of Science Policy & Governance (JSPG) in collaboration with Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy-Science and Technology Policy Program organized a workshop featuring winning authors from the JSPG Special Issue on Shaping the Future of Science Policy in partnership with the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and sponsored by the Kavli Foundation, published earlier this year. This event provided a framework for early career voices to be heard in advancing a better future by responding to the OSTP ideation challenge “The Time is Now: Advancing Equity in Science and Technology.” During the workshop, participants crafted a joint response to the challenge, which was submitted to OSTP, encompassing early career voices. This blog post contains responses from the event coming from winning published authors and other early career participants. The event was framed by remarks from Dr. Sudip Parikh, CEO of AAAS and also JSPG advisory board member, who co-authored the cover memo for the Special Issue with Dr. Cynthia Friend, President of the Kavli Foundation. Below is a quote from Dr. Sudip Parikh from the video. "It is always exciting for me to see people contributing to the future of Science and Technology Policy. But it's especially exciting when it's early career scientists and engineers who are going to be directly affected by the policies that we put in place now. Also excited by the fact that you're working with JSPG to take your ideas into action through this challenge. I'm looking forward to seeing some of your policy and act ideas enacted right away through this challenge, but also in the future.“ - Dr. Sudip Parikh Panel discussion Winning authors from the policy position paper competition participated as panelists and discussed their publication in the special issue, including their ideas of how OSTP can address these issues, and led breakout rooms to reimagine a more equitable future for science and technology policy in relation to their publication topics. The panel discussion was moderated by Senior Policy Advisor at the MIT Washington Office, Dr. Kate Stoll, who has long been interested in the role of students in the research and innovation enterprise. Below are summaries of ideas related to each publication topic from winning authors and other early career researchers who participated in the event, and contributed to the OSTP submission in response to this challenge. Inclusive Science Policy and Economic Development in the 21st Century: The Case for Rural America Event recording Publication Special Issue

Background: The publication captures inclusive science policy and economic development, with a focus on rural America. Scientific research over the 20th century brought many benefits for society. But this innovation ecosystem is not accessible to everyone in the United States. Problem and solution: There is a clear divide between rural and non rural areas in access to science innovations, and who can benefit from these innovations. The publication argues that rural development initiatives could be more broadly reframed as a form of science policy, focusing on education as one policy silo. Some proposed solutions are that we need more sustained federal investment in rural communities, and maximizing the effect and the investment for rural education both at the K 12 and higher ed levels. It also covers diversifying the economy in rural locations. What OSTP can do: There should be a more coordinated federal investment to rural communities. It would be really interesting for OSTP to step into that space and invest more in inclusive approaches to science policy. Rural development could, in many ways, be reconceptualized, as science policy, or science policy, being an important facet of rural development could be really interesting. OSTP could link these threads together, and help deliver innovations that come from this investment into various geographic corners of the country. A Call to Diversify the Lingua Franca of Academic STEM Communities Event recording Publication Special Issue

Background: Science is better when more people can participate. In STEM academia, there is an enormous burden on individuals who do not speak English as their first language, including a financial burden to translate their works into other languages, if they are going a bilingual route. Problem and solution: This problem causes quite a bit of homogeneity in science. But it is also detrimental to U.S. science, because not all of the world in science can publish in English. We propose that there should be structure from a top down level for hosting and translating science into different languages. Some of the specifics to consider include, how to choose which languages to translate into. There is also a critical point at which it becomes detrimental to be publishing in too many languages, and we cover this balance in the paper. What OSTP can do: A proportion of federal grants that are given to researchers could go towards paying for translation services. Government agencies could negotiate better rates for people who are seeking translations for their papers. Translations are quite expensive, sometimes up to $10,000. Standardization for translations would be really excellent, in terms of ways to maximize resources and increase transparency. Demographics of science and language diversity in science is not well documented, and not well known. It would be really nice if there were dedicated resources to keeping track of this type of diversity. We propose adding a question to federal grants that asks about the language that researchers speak other than English. This would allow for evaluating this diversity over a longer period of time. Ensuring Social Impact at Every Stage of Technology Research & Development Event recording Publication Special Issue

Background: Publications are the fundamental backbone of science. As graduate students, we read a lot of papers, and recognize the value that some publications can provide to science advancement and society on a high level. Many of us want to have some kind of meaningful impact on the world, but often the results of research can seem somewhat divorced from the long term impact of science and technology. A large number of publications sit on the proverbial shelf after they’re published, and never influence any kind of real-world developments. As such, when the average person thinks about the development of science and technology, they rarely consider the research process.

Problem and solution: Funding agencies like NSF attempt to use broader impact criteria to evaluate this research and the societal impact, but the criteria are assessed by the same scientists assessing the scientific merit of the proposal. These scientists are not usually in the best position to judge the long term impact of a research proposal, which may go on to affect a large number of different stakeholders. Therefore, I argue in my paper for including these affected stakeholders when judging potential long-term impact, and using those judgments to help determine which proposals to fund. My hope is that this will eventually better connect the public to research, help them to better understand the research process, and ultimately help research be more responsive to their concerns. What OSTP can do: My hope in the long term would be that by bringing different public stakeholders into judging research, that they'll be more aware of what it takes to actually produce some kind of science and technology innovation from the very beginning. And so doing, they'll understand and evaluate research better, and that research will be more responsive and attentive to their particular concerns. OSTP can draw up a framework by bringinging stakeholders together for particular research areas, such as the general public, journalists. Then also developing some online courses for these stakeholders to evaluate research in different disciplines. Overall summary: To conclude, Dr. Kate Stoll, who moderated the panel, said she was inspired by all three authors in that “the assumption that the status quo doesn't have to persist: we know we can do science better; we know there are specific and actionable ways to make the scientific enterprise and its outcomes more inclusive, and now what we need is the follow through, so these ideas are a great start to that process and this challenge is a great way to engage.” Event participants: Andrew Crain*, Director of Experiential Professional Development, University of Georgia (UGA); PhD candidate, UGA Institute of Higher Education Claire Cody, graduate student, Yale University David Lockett, K-16 Outreach/Grants Proposal Development Specialist School of Applied Computational Sciences, Meharry Medical College Ravichandra Mondreti, Independent Researcher and Consultant, Bengaluru, India Lindsay DeMarchi*, graduate student, Northwestern University Kristifor Sunderic, AAAS STPF, National Cancer Institute (NCI) Mohammed Baaoum, graduate student, Virginia Tech Shakiyya Bland, Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellow, U.S. Department of Interior Jeremy Pesner*, graduate student, Carnegie Mellon University Nicole Comfort, postdoctoral researcher, Columbia University Sonia Roberts, postdoctoral researcher, Northeastern University Surangi Perera, postdoctoral researcher, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Adriana Bankston, JSPG CEO & Managing Publisher (organizer) *published authors and competition winners We would also like to thank Dr. Kate Stoll for moderating the panel and contributing to the discussions. This post was written and compiled by Adriana Bankston. Introduction

On October 26, 2021, the Journal of Science Policy & Governance (JSPG) organized a science communication and outreach workshop for winning authors from the JSPG Special Issue on Shaping the Future of Science Policy in partnership with the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and sponsored by the Kavli Foundation, published earlier this year. The goal of the workshop was to empower JSPG early-career authors with tools for communicating their research and policy papers more broadly to engage policymakers and the general public. This effort is part of JSPG’s initiative to leverage work published by early career authors in policy discourse and debate, and take these ideas beyond the publications. View the workshop recording. Format The workshop was led by Lisa M.P. Munoz, president and founder of SciComm Services, a full-service science communications consulting firm. During the workshop, Lisa gave an introductory presentation covering the importance of science communications, ways of identifying audience and goals, elements of a good “pitch,” tips for creating versatile research/policy pitches, and how the authors can make the most of their pitches. Authors then gave lightning pitches on their publication abstract, and received feedback from Lisa. Finally, authors worked on crafting and refining their pitches into a short paragraph (100-200 words) in groups. Lisa then provided more feedback on these pitches, which are listed below. These pitches are a good example of ways to engage desired audiences with policy ideas put forth in JSPG publications. Resulting pitches (*workshop participants) Andrew Crain* - Inclusive Science Policy and Economic Development in the 21st Century: The Case for Rural America Even though college degree attainment is on the rise nationally, the gap in degree attainment between rural and urban communities is actually increasing. The fact is that a child growing up in rural America does not have the same life opportunities to engage in the innovation economy of the 21st Century. This is true in terms of important infrastructure such as healthcare and broadband internet, and it is true of economic opportunities like high-growth industries and STEM education. I argue that this is a pressing policy issue that has to be addressed. By focusing on STEM education, I propose a number of policy changes that could enhance access to the innovation economy for rural students. These changes include more investment in STEM education in rural K-12 schools - for example, STEM preparatory and AP coursework - more investment in rural-serving colleges, and more geographically-inclusive approaches to funding scientific research and knowledge start-ups. Each of these strategies could lead us toward a future where economic opportunity is more available to all - regardless of their geography. Carolyn E. Ramírez* - Without Environmental Justice, the Renewable Energy Transition Will Leave Low-Income and BIPOC Communities Behind As extreme weather events become more common in the United States due to the worsening effects of climate change, access to utilities like electricity and water will be continually strained. Climate change most negatively impacts environmental justice communities: low-income and communities of color. While renewable energy technologies promise alleviation of emissions and pollution, high cost and a lack of equitable energy infrastructure make it harder for environmental justice communities to access renewable energy benefits. As a chemical engineering researcher studying renewable energy technologies, I propose a series of policies to level the field in terms of household and utility infrastructure for all communities including significantly increasing funding to existing federal weatherization programs, implementing consumer protections, and establishing local task forces to increase stakeholder buy-in to renewable technologies. Jeremy Pesner* - Ensuring Social Impact at Every Stage of Technology Research & Development The US spends over $450 billion annually on research, but how can we ensure that this research actually helps us improve our country, much less the lives of all its citizens? Most research funding, review and execution is only undertaken by scientists, with minimal understanding by, transparency to and input from outside stakeholders. For example, stakeholders for advances in legged robotics may range from geoscientists (for field research on desertification) to the military (for supporting soldiers in rough terrain) to potential victims of police brutality (if the police benefit from these robotic advancements). Research often leads to many new technologies and innovations, but those whose expertise and lives are intertwined with them, such as policymakers, educators, VC investors and underserved citizens, all need to help guide the research from the very beginning. These stakeholders must judge the potential impact of research proposals to establish clear expectations of how research that is selected for funding will benefit everyone in the long run. While scientific novelty is an important criteria to consider when funding research, it cannot be the only one, and must be balanced against larger societal concerns as well. Kaylee R. Henry*, Ranya K.A. Virk*, Lindsay DeMarchi, Huei Sears* - A Call to Diversify the Lingua Franca of Academic STEM Communities Imagine writing an article in Chinese and winning the Nobel prize for this work, but then you only get cited ONCE outside of China. This happened to Tu Youyou - instead, an English summary of her work was cited over 500 times! To prevent this from happening again, we propose that all scientific journal articles be published in at least two languages. In our multilingual world, it is unfair that English is so highly prioritized and this is built into the current infrastructure of academic publishing. By publishing science in at least two languages, we would improve international scientific communication to help solve complex, global issues such as climate change, and emphasize the importance of all researchers, regardless of language. Vetri Velan*, Rachel Woods-Robinson*, Elizabeth Case, Isabel Warner, Andrea Poppiti, Brian Abramowitz - The Federal Science Project: A Scientist in Every Classroom Imagine if every classroom in the US was visited by a practicing scientist or engineer, every year. When I was growing up, I’d never met a scientist. It wasn’t until I did that I could envision myself in a career in science and see science as a way to solve global challenges like climate change. We propose a program called The Federal Science Project to deliver this opportunity to every student. As of now, most outreach programs are concentrated in cities or around big institutions, so there is a barrier to access, which exacerbates inequities in STEM. But with our program, federal, state, and local governments would build a nationwide network to connect scientists with teachers and schools. This network would allow students across the country, regardless of geography, race, ethnicity, class, or other barriers to meet scientists. Such a program would radically transform the way in which scientists engage with society, and in turn how students learn about science in school. This post was written and compiled by Adriana Bankston.

On May 29 & 30, 2021, the Journal of Science Policy & Governance (JSPG) and the Global Young Academy (GYA) held a joint virtual science policy memo writing workshop for early career researchers all across the globe. The goal of the workshop was to equip early career researchers with the essential tools needed to write effective policy memos. During the workshop there were several presentations to introduce JSPG and GYA, followed by a keynote presentation from Dr. Doyin Odubanjo, Executive Secretary at the Nigerian Academy of Science. Over the course of two days, the workshop gave participants the opportunity to draft an outline of a science policy memo and receive feedback from policy experts.

The workshop had a presence from all around the world. There were 70 participants that represented over 20 different countries. The participants came together across different time zones to develop skills for writing science policy memos on topics related to the 2021 GYA Annual Conference theme “Trust in Science.” Day 1 was full of presentations and our first breakout activity. Dr. Nicole Parker, JSPG’s Director of U.S. Outreach, provided participants with an overview of the journal and opportunities to publish. This was followed by a presentation from Dr. Felix Moronta Barrios, member of GYA and former co-lead of the Science Advice Working Group, introducing GYA and the Science Advice Working Group. Both JSPG and GYA are organizations focused on early career engagement, and the participants were provided with many resources to get involved.

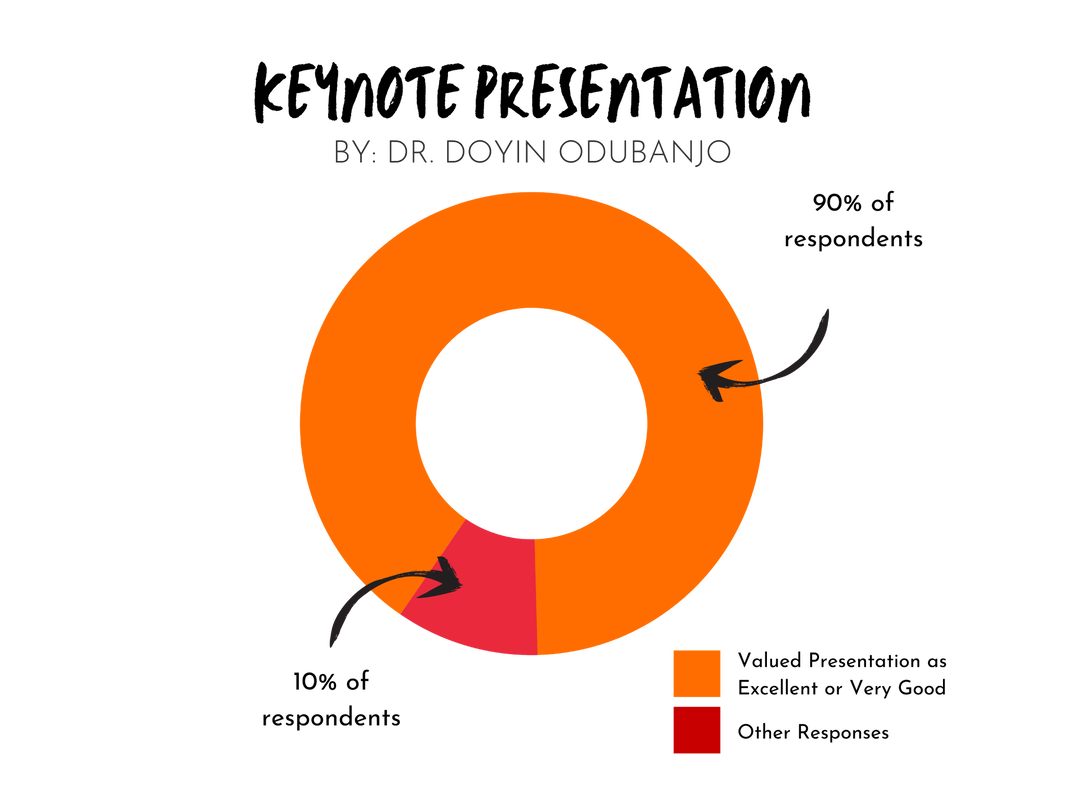

The keynote presentation from Dr. Doyin Odubanjo focused on the intersection between science and policy making. He provided several tips on how to write an effective policy memo including but not limited to using simple language, providing evidence, and being succinct. Throughout the presentation he emphasized the importance of knowing your audience and conducting stakeholder analysis prior to writing the memo. The presentation also included several case studies from the Nigerian Academy of Science to emphasize writing skills.

Following presentations, the remainder of day 1 and day 2 were filled with an opportunity for participants to work in groups to develop outlines for their science policy memos on “Transforming Food Systems: Public Trust and Engagement to Reach the UN SDGs” and “Science Policy Advice - Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic.” These were two of several topics for the 2021 GYA Annual Conference on “Trust in Science.” Both topics resulted in a robust discussion led by our moderators, many of whom were GYA members. The participants were able to draft a memo outline on day 1, which was reviewed on day 2 for expert feedback. The workshop was extremely helpful in building confidence for our participants in writing an effective and impactful science policy memo.

Following the workshop, organizers assessed the impact amongst the participants with a survey. There was an overwhelmingly positive response to the workshop and many participants felt it was very useful. Nine out of ten participants rated the presentation by Dr Doyin Odubanjo as excellent or very good. The usefulness of practical exercises, of moderation with experts, and the insights provided by reviewers were also highly appreciated by all participants.

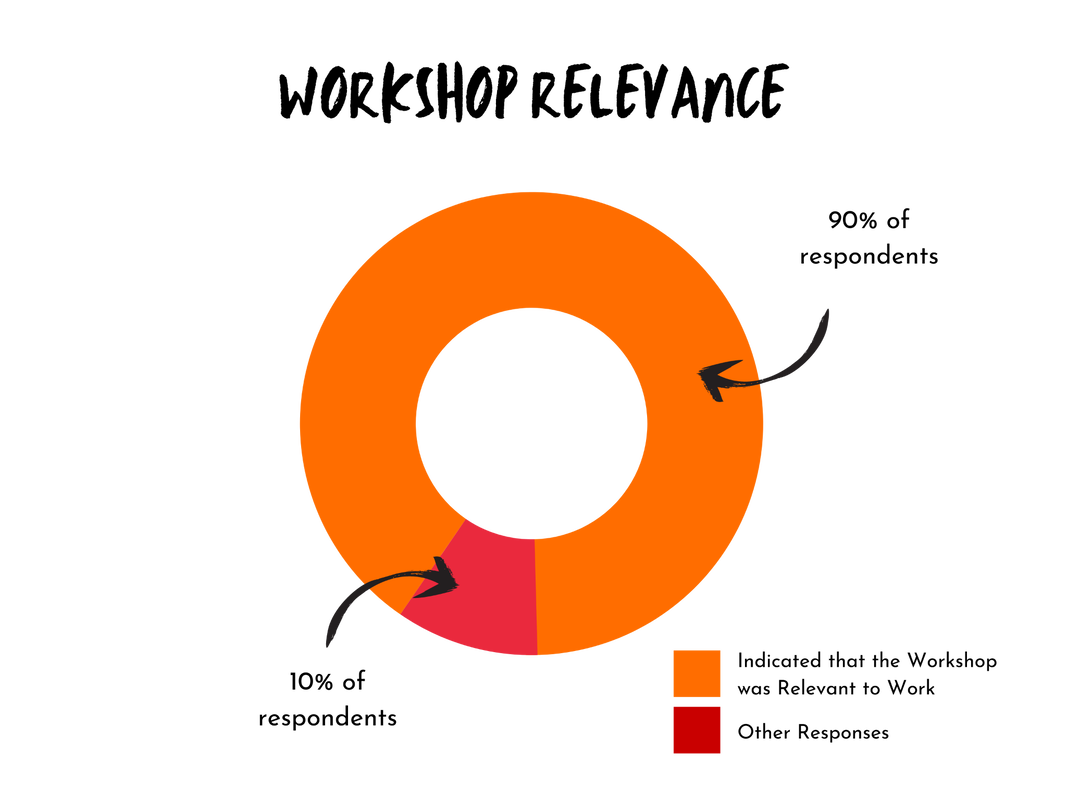

Participants also indicated that the workshop was highly relevant to their work and provided some testimonials.

This was my first time attending a workshop on Policy Memo writing. I was always very confused and irritated by the way the information on the internet is available but this workshop cleared all my doubts and removed the barrier for starting to write a memo about my own research area. I really appreciated breaking the memo down into key parts to get us thinking and make it easier to tackle.I was worried that the breakout rooms were going to be awkward/hard to engage with but they ended up being great! Small groups with a clear moderator and clear format/goals really helped.

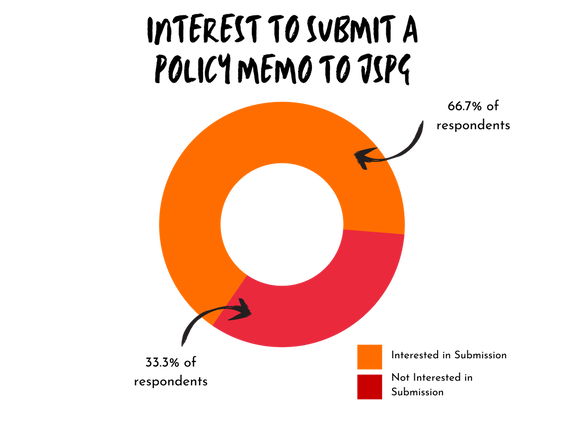

Finally, two thirds of participants expressed an interest in submitting a policy memo to JSPG.

This writing workshop was a very fruitful and exciting collaboration between two organizations dedicated to early career researchers. To watch the full workshop visit JSPG’s YouTube page. If you’re interested in writing a science policy memo, submit your ideas to our next standard issue by November 14, 2021.

Article written by Dr. Nicole Parker, JSPG Director of US Outreach, in collaboration with Dr. Felix Moronta Barrios, former co-lead of the GYA Science Advice Working Group.

It has been a privilege to be a part of JSPG's growth - the journal began as a collection of insightful science policy submissions by early career scientists, and over ten years it has become an impactful journal that is building a community of highly engaged international science policy scholars and advocates.

In the previous post, we spoke with authors who published in the first issue of JSPG.

In this second post, we also talked with our editorial leadership who have had a long tenure with the journal to hear their reflections and ideas for the future.

Past editorial leadership: how did JSPG help advance their careers?

Gary Kerr and Tess Doezema both led the editorial process for a number of years, and discussed how the journal helped them grow professionally:

Gary:“Leading the editorial board at JSPG has helped me develop not only as an editor and leader, but has opened up a huge range of professional opportunities for me. JSPG has helped me understand in detail the policy-making process, and as a result I’ve been able to advise the Scottish Government on COVID-19 policy, and more recently been appointed to a panel of experts on science communication at the European Parliament. Without the direct science policy experience developed at JSPG, these doors would not have opened for me.”

Tess:“My role as JSPG Editor-in-Chief gave me the opportunity to develop and enact my own editorial vision, allowing me to gain invaluable insights into the writing and publishing processes and experience managing a diverse and geographically dispersed team of editors and authors. My time with the journal continues to inform how I approach student mentorship and science communication across communities and disciplines. Beyond these more practical skills, what I learned as part of the JSPG team continues to productively shape the knowledge and experience I bring to conceptualizing the complex interplay between knowledge and policy, between technologies and the worlds their creators imagine to exist and seek to intervene in.”

More recent editorial leadership: how does JSPG help the next generation?

More recent leadership by Christian Ross took the journal to the next level, alongside our expansion in the number of special issues led by Maddy Jennewein. They reflect on the value of the journal for the next generation:

Christian: “The next-generation of science and technology policy researchers and practitioners have an invaluable resource in what JSPG has accomplished. As a journal, JSPG provides an exceptional platform to engage with dynamic and complex topics in science and technology policy that are incredibly consequential. More than that, JSPG gives early-career researchers opportunities and experiences that distinctively equip them for academic and professional careers in which science and technology are increasingly and rightly recognized as being inseparable from the social, cultural, and political realities of the worlds we create and live in. For myself, leading the editorial team at JSPG has enabled me to better understand and navigate policymaking contexts and enhanced my own professional work in ways that would not have been possible without the unique position of JSPG at the intersection of science, technology, and democratic governance.”

Maddy: “JSPG provides a unique resource for developing scientist-researchers. As the journal has grown we’ve been able to expand not only the editorial support we’ve provided but also the outreach and resources to the broader community. Particularly as the special issues side of JSPG has expanded over the past 4 years, we’ve greatly increased the number of submissions that we published, engaging more authors and more importantly widening the pools of authors that we support to a more global and diverse place. Partnering with organizations such as the National Science Policy Network and the UN Major Group for Children has brought us much greater prominence in the space, and attracted a broad pool of authors and editors to join our effort. Working with JSPG over the past several years has been a wonderful experience and I’ve truly enjoyed working closely with Tess and Christian to help grow the journal and solidify new practices and procedures to enable a more successful journal.”

Editorial reflections on the future of the journal

Looking ahead, Rosie Dutt recently became our newest Editor-in-Chief. She shares her hopes for the future:

Rosie: “As the journal has continued to grow from strength to strength, I endeavour to keep the momentum going by fortifying the journal's editorial board through refining our review process to ensure maximum efficiency and the publication of high quality articles that continue to elevate early career work and voices in science policy.”

Brand new Assistant-Editor-in-Chief Ben Wolfson and Junior Assistant-Editor-in-Chief for Special Editions Andy Sanchez, also shared their perspectives:

Ben: “As a long time associate editor it was a privilege to support so many early-career researchers as they’ve entered the policy arena and a pleasure to read their diverse work. It’s been both incredibly interesting and an inspiration for my own science policy journey. JSPG is an incredibly valuable resource and I’m excited to support the journal's future growth as Assistant Editor-in-Chief."

Andy: "JSPG fulfills a key role in the science policy landscape, by providing early career researchers an outlet for policy issues they're passionate about. Through the editorial process, our contributors hone their skills in policy, communication, and critical thinking. Afterwards, they can use the published product to advance their advocacy--spreading awareness about their projects with an accessible, actionable document. I was thrilled when I first published in JSPG, and now, in my new role, I'm honored to support the journal's mission and help our authors realize their goals."

In closing, we are grateful to our authors for their interest in the journal and to the editors for supporting the journal during these 10 years. We’ve also been very fortunate to be surrounded by many wonderful peers and mentors in our editorial board and editorial leadership teams, and guided by an illustrious group of thought leaders in science policy through our governing board and advisory board. We thank them all for their input and dedication in making the journal what it is today, and we are also grateful to our partners who have supported us over the years and helped move our common missions forward. We look forward to taking the journal to new heights in the next decade, based on this solid foundation laid before us.

Post written and compiled by Adriana Bankston.

The next 10 years will bring bigger, bolder and more entrepreneurial policy ideas than ever before. We look forward to continuing to elevate published work and early career voices on the international stage, while building upon a solid foundation of innovative writing and publishing laid by those who came before us. When JSPG was first established, the ecosystem supporting the involvement of early career STEM professionals in policy ideation and implementation was far more limited. I’m deeply humbled by the work we have all accomplished through JSPG worldwide over ten years--the diversity of voices and the ideas we’ve elevated. Now more than ever, we need substantive vehicles like JSPG to continue to empower the new generation to shape the frontiers of science, technology, and innovation policy and governance.

In June 2011, the Journal of Science Policy & Governance published its first volume. To celebrate the 10 year anniversary of the first issue, we took a look back in time and reflected on how far we’ve come, in this two-part blog post.

Over these 10 years, we have published 18 volumes and several special issues. We have trained and mentored countless numbers of students, postdocs, early career researchers and policy fellows from all over the world, and grown our impact through the sheer dedication of our staff, editors, governing board and advisory board members.

The welcome statement for this first issue stated the purpose of the journal as: “A publication dedicated toward identifying emerging challenges and exploring novel solutions. All of the articles are authored by students and young scholars, who provide a unique and often undervalued voice in policy debates.” I would argue we’ve done all that and more. We’ve stayed true to our mission, but grew our impact internationally beyond what we could have dreamed at that time. For 10 years, the journal has given birth to some of the most innovative policy ideas, and we’ve been inspired by the next generation’s views on the future of the field.

First issue published authors: where are they now?

This first issue covered many different topics in science, technology, governance, and policy in several formats, much like we do today. But this date will always mark the beginning of a new era in policy making when a journal focused solely on the next generation of policy leaders was born.

For this post, we caught up with some of the authors from the very first published issue, and learned about where they are now.

Firas Midani published a policy analysis on Advancement of the Multidisciplinary Research Paradigm via Facilities and Administration Costs and Cost Recovery Incentives. Currently he is a Postdoctoral Fellow, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

Firas:“When I published in the inaugural issue of JSPG, I was debating whether to fully pursue scientific research or science policy. I recall chatting with Max Bronstein, founder of JSPG, on careers in science policy. He made an incredibly valid point that academic scientists can still engage in science policy at different stages of their career and indeed make an impact doing so.

I eventually earned my PhD in Computational Biology at Duke University and I am currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. My research investigates how what we eat can influence the gut microbiome, the collection of microbes in our intestinal tracts, and accordingly influence our health. In particular, I am interested in how diet can protect from infectious microbes that cause incredible burden both in the Western world and developing nations. After a decade in academic science, I now have a different perspective on science policy including additional thoughts for my JSPG publication on the utility of indirect costs for incentivizing multi-disciplinary science. Over the next decade, I hope to incorporate this newer and enhanced perspective as I engage with policy leaders to shape the scientific enterprise and influence global policies.”

Matt Wenham was completing a postdoc at the NIH and volunteering as a Science Policy Fellow with Scientists and Engineers for America when he and one of his policy interns, Trisha Lowe, published an analysis of policy approaches to groundwater in South Florida.

Matt: “I used the opportunity provided by the SEA fellowship and publication in JSPG to springboard my career from the lab into science policy.”

Subsequently he moved to a Washington DC-based think tank, the Institute on Science for Global Policy, as an Associate Director. Returning to his native Australia in 2013, Matt became director of policy at Australia’s national academy for applied science, technology and engineering. He is currently an S&T policy manager for the Australian Department of Defence.

Aaron Ray published an article on Adaptive Policy Approaches to Ocean Acidification in this issue. He later served as Assistant Editor-in-Chief for JSPG.

Aaron: “Publishing in and later editing articles for JSPG was a great opportunity for me to share my research and contribute to the broader community of science policy scholars. It was a great introduction to the academic publishing process.”

Following his contributions to JSPG, Aaron served in the White House Office of Management and Budget with responsibility for Department of the Interior science and natural resources programs. He is currently a Deputy Director for Policy at the Colorado Governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting.

Connect with Aaron on LinkedIn.

We are grateful to be able to look back to the first issue and reflect on where we are now and what we’ve published over these 10 years and ways in which we’ve elevated the next generation in policy. This has been made possible through our talented editorial team. In the next post, we will hear perspectives from the JSPG’s editorial board and leadership.

Post written and compiled by Adriana Bankston.

INTRODUCTION In this post, we discuss Dr. Jennifer Pearl’s career path through which she has made significant impact in both the science and policy landscape and enterprise in the U.S. Through leadership positions with the AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellowships Program (AAAS STPF), the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), and the National Science Foundation (NSF), Jennifer’s career spans multiple types of roles in different sectors of society. Read below for a description of Jennifer’s career path, and a Q&A where she reflects on her professional experiences and provides advice for the next generation of science policy leaders.  Author Bio: Dr. Jennifer Pearl is a mathematician and Science and Technology Advisor for the Directorate for Engineering at the National Science Foundation. Prior to this role, she served as the director of the Science & Technology Policy Fellowships program at the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She has also held positions at the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine and at Rice University. She earned her Ph.D. in mathematics in the field of symplectic geometry from the State University of New York at Stony Brook and a Bachelor of Science in mathematics from Duke University. Photo credit: AAAS / Kat Song. CAREER PATH

Leaving academia to become a policy fellow Following her PhD training in mathematics, Jennifer took the postdoc route continuing with research and teaching. After a few years, she realized that she wanted to work on problems that were broader than the ones she was tackling in her research career. Through volunteering in the tech transfer office at Rice University, she learned about intellectual property and later engaged in consulting. This experience provided her with a way to learn about the combination of business, law and science. She took a position working for the Dean of Natural Sciences at Rice University, where she developed a new professional master's program funded by the Sloan Foundation. During this time, she helped to create a science policy course for masters students, where she worked with former NSF and OSTP Director Dr. Neal Lane. Dr. Lane encouraged her to apply to the AAAS STPF. She was accepted into the program, and completed her fellowship at the NSF. Through the fellowship, she developed relationships with scientists and engineers who remained her colleagues for many years. She would later return to NSF, where she currently works. From being a AAAS STPF fellow to the NASEM and NSF After her AAAS policy fellowship, Jennifer took a position as Program Officer with the Board on Mathematical Sciences and Their Applications (now the Board on Mathematical Sciences and Analytics) at the NASEM, where she worked on studies commissioned by different government agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, Department of Energy, and Department of Defense. These projects taught Jennifer to determine the right people to recruit on committees, as well as the right questions to ask in order to make sure that all relevant voices were represented. At the NASEM, Jennifer also built important professional relationships. Following her role at the NASEM, Jennifer became a Program Director in the Office of International Science and Engineering at the NSF, where she fostered international collaborations for U.S. researchers and students, and interacted with staff at counterpart foreign funding agencies and embassies in DC. She then transitioned to the NSF’s Division of Mathematical Sciences, where she led programs to support the mathematics and statistics community in the U.S. During this time, she engaged in several professional development experiences, through what is called a “detail,” taking a stint as the Acting Deputy Division Director and leading an effort to understand partnerships for the NSF Office of the Assistant Director for Mathematical and Physical Sciences. These expanded her knowledge and capability, giving her exposure outside her immediate unit. Following her role as Director of the AAAS STPF Program (in the section below), Jennifer returned to NSF as Science and Technology Advisor for the Directorate for Engineering, which is her current position. In this role, Jennifer is responsible for identifying partners across sectors with similar interests and complementary strengths, and engaging them to advance projects related to engineering research and education. These partners may include other domestic or foreign government agencies, private foundations or industry entities. In addition to developing collaborations with these partners, Jennifer also participates in broader NSF-wide efforts on relevant science and science policy topics. Leading the AAAS STPF Program Prior to her current role at NSF, Jennifer was the Director of the AAAS STPF Program, the fellowship program which brought her to DC in the first place. In describing her experience leading the program, Jennifer noted that it was exciting to see this tremendous demand for fellows in federal agencies, and to observe the downstream effects of the fellowship on the careers of alumni over the last 50 years. In this role, Jennifer enhanced the program through building partnerships to support fellows in Congress and led an effort to make the program more data-driven. As part of the latter, she and her team developed a logic model for the program and commissioned the first comprehensive fellowship alumni evaluation to quantify impacts. In terms of challenges for running the program, Jennifer mentioned the need to run a unified initiative while coordinating among the large number of stakeholders, including fellows, government host organizations, partner societies, funders, and the terrific staff that make the whole operation run. CAREER Q&A You’ve held several impressive positions throughout your career. What drives you to look for those positions, and do you have a long-term career plan? I'm a mathematician by training, and I like to look at spaces that are complicated and messy, and put some structure on them. I like to figure out where the opportunities are and where I can have a positive impact. I also look for positive environments where there is a fun problem to solve. And I don't have a career plan - I just look for interesting problems to solve and good people to work on them with. In general, I seek to meet people outside my current work unit or current organization, and try to stay open to professional opportunities. How has university training been beneficial to your overall career path? I think an understanding of the research and education process is key to more broadly supporting the science and engineering enterprise. My academic experience has certainly informed my work in all of my positions. And, as they say, a Ph.D. gives you five minutes of credibility in larger discussions. In addition to my background in mathematics, experiences with tech transfer and program development in the university space have provided a broader understanding of how the system functions through exposure to offices outside of traditional academic departments. Which skills should early career researchers develop if they're interested in a science policy career, or in some of the roles you’ve held in your career? Both oral and written communication skills are very important. Scientists are usually trained to generate and test hypotheses. However, once you get out of your immediate research space and you're looking to define, implement, or re-envision an initiative, you have to figure out who the main players are, and how to get them on board. So I would suggest that folks seek out that kind of experience even in a volunteer role. In general, when giving career advice, I always advise early career researchers to look for and say yes to new opportunities. Not all jobs will be your dream job, but in any position there will be colleagues you can collaborate with and skills you can learn to help you move to your next role. Can you recommend resources for early career researchers interested in science policy careers? I would encourage you to look at the Journal of Science Policy & Governance (JSPG) as a place to publish your policy work, get involved in the science policy section of your disciplinary society, engage with the National Science Policy Network (NSPN), and see what policy resources your university offers. Locally you can also volunteer on policy-related efforts, and get to know your university’s government affairs office for specific connections. More broadly, consider a science policy fellowship like the AAAS STPF or state fellowships, including the California Commission on Science & Technology (CCST) Fellowships Program. I would also read reports such as the Science Policy Career Guide published by CCST, and a blog post by AAAS STPF fellow Steph Guerra, Finding your science policy path is also a helpful resource. Finally, follow science policy social media handles on Twitter, especially @AAAS_STPF, @SciPolJournal, @scipolnetwork, @scipoljobs and others. Disclaimer: This post represents Jennifer Pearl's personal views and does not reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Post compiled and edited by Adriana Bankston.

INTRODUCTION

With support from The Kavli Foundation, the Journal of Science Policy & Governance (JSPG) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) have launched a call for policy position papers and competition in recognition of the 75-year anniversary of Science: The Endless Frontier. The competition seeks to uplift and empower the next generation of science policy professionals to publish policy position papers that could shape the future of American science. JSPG interviewed a series of early career researchers and science policy experts, including Sudip Parikh, Marcia McNutt, Neal Lane and Deborah Wince-Smith who shared their hopes for the future of American science and tips for shaping U.S. science policy, respectively. In addition, JSPG organized a series of six webinars to inspire and help authors with their writing for the call for papers. To close out the competition, JSPG provided the opportunity for one early career individual attending each webinar to be featured in this post and share their overall impressions and takeaways from our six webinars. Below are summaries of each webinar in the series in order, from an early career participant (graduate student, postdoc or early career faculty).

STRATEGIZING FEDERAL U.S. RESEARCH INVESTMENTS TO MAXIMIZE ECONOMIC AND SOCIETAL IMPACT

Watch the webinar here

What drew you to attend?

With the renewed commitment to the US scientific enterprise and the commemoration of the publication of “Science The Endless Frontier” by Vannevar Bush, I was enthusiastically optimistic to see the webinar series, sponsored and organized by the Kavli Foundation, JSPG, and AAAS, “Science The Endless Frontier: the Shaping the Future of Science Policy.” I was particularly attracted to the first webinar entitled “Strategizing federal U.S. research investments to maximize economic and societal impact.” The panel was moderated by Toby Smith and highlighted four distinguished scientists and science policy experts. Takeaways from speakers With his expertise in technology transfer, Marc Sedam approached the questions from that perspective. He stated that the US continues to be impacted by the “Valley of Death” in regards to science and technology transfer. Universities have established innovation centers and startups in an attempt to close the research-development gap, but this has only shifted the gap. Scientists and funding agencies can help this process by finding uses for ideas and ways to commercialize those ideas. Susan Renoe is an expert in research engagement. She highlighted that structural changes in the scientific enterprise are needed that can be integrated through broader participation and engagement, particularly with STEM education. More impactful activities and better and longer-term assessments of that impact need to be incorporated into the process. Along the same lines, Mahmud Farooque suggests that science needs to move beyond just inputs and outputs, and focus on outcomes. Science outcomes need to continue to be evidence-based and action-oriented. He highlighted that Science: The Endless Frontier is a guiding document but has not created a transformational shift in societal and equity changes. The scientific enterprise needs to think about “what does society need?.” Daniel Goroff advocated that science works better when social, behavioral, and economic sciences are engaged earlier in the scientific process. These types of sciences have strong methodologies, which can be used to design experiments that inform and test policy implementation. He concluded that sciences are uniquely equipped to provide broader impact and provide policy makers with evidence-based information. Overall takeaway The overall consensus of the panel is that the scientific enterprise and systems need to be viewed differently at all levels of academia, industry, government, and the public, and updated through broader engagement and accessibility at each level, such as the development of national research excellence framework, and science for and with society through participatory citizen involvement. Social, behavioral, and economic science should be incorporated into all levels of research, such as looking at the societal value of research and the role it plays in leading to qualitative methodologies, and to the commercialization of research ideas. Additionally, scientists need to think about the broader impact of their work. Policies, such as national research excellence frameworks, can be established to promote engagement and accountability with the public through increased funding and awards to scientists that incorporate this into their research activities.

What drew you to attend?

In the past year, I saw the impact of COVID-19 not only on our health, economy, and social norms, but also in the great societal divide in how to best address the problem. With limited information available about the virus came the conflicting opinions among the medical and public health communities on the specific guidelines for the public to follow. I was intrigued by the challenge that everyone involved in science policy faces when approaching a public health problem as complex as COVID-19. For this reason, I jumped at the opportunity when I heard about JSPG-AAAS’s special topics call for policy position paper submissions to “The Endless Frontier: Shaping the Future of Science Policy,” to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Vannevar Bush report. In preparation of the submission, I attended the writing workshop hosted by JSPG and AAAS to learn about the structure and style of a policy position paper which I have never written before. Attending the webinar series post-workshop seemed like a next logical step in understanding how insights from scientific research can inform policy making. The panel was moderated by Erin Heath and highlighted four public health policy experts. Takeaways from speakers The timeliness and relevance of the webinar topic made it easy to engage in the discussion. We saw COVID-19 vaccines being developed at an unprecedented speed, yet the U.S. population has not taken full advantage of it due to the lack of delivery infrastructure and growing public mistrust in science. What can we do to improve the system moving forward? The priorities in investment were discussed extensively. I agree with Carrie Wolinetz that the biomedical research enterprise requires conscious investment in promoting workforce diversity and building community relationships in science. We should learn from the consequences of the pandemic, which disproportionately impacted women and people of color. Additionally, Tannaz Rasouli and Jennifer Luray mentioned the importance of a more sustained investment in public health infrastructure for CDC, as well as no more “sugar coating” of this message to the public. Robert Cook-Deegan also had a good point about the need to move away from research conservatism that tends to prioritize funding studies with immediate benefit. Without decades of fundamental research, the COVID-19 vaccines could not have been developed so rapidly. Understanding that money alone does not solve all problems, I asked the question of, “what are some non-monetary ways to improve the US public health infrastructure to better respond to public health threats?.” The panelists offered helpful insights such as breaking barriers for early career scientists in academia, open data sharing for increased transparency, and monitoring institutional behavior for improved collaboration. I appreciated these answers because they highlight the need for an inclusive and collaborative culture for creating an effective strategy to combat national public health crises. Overall takeaway I think early career scientists would benefit from participating in public health policy discussions by identifying key unanswered questions that require further research. As a neuroscience graduate student, I found this event an excellent opportunity to explore a potential career in science policy and a nontraditional way to extend my expertise and skills to make a tangible societal impact. As we celebrate the scientific achievements and learn from our mistakes, we will have more productive solutions to future public health challenges.

STRENGTHENING AMERICAN UNDERGRADUATE AND GRADUATE STEM EDUCATION AND TRAINING

Watch the webinar here

What drew you to attend?

My passion centers on improving STEM education, and I am also avidly engaged in activities at the intersection of science policy and science communication. Because my day-job centers on broadening participation in STEM higher education and the webinar speakers are prominent leaders in this arena, I knew this event would identify major limitations to current higher education models and yield notable ideas on how to improve the nation’s STEM enterprise. The panel was moderated by Kate Stoll and highlighted three experts in STEM education and policy. Takeaways from speakers Vannevar Bush recognized that the greatest scientific resource we have is the intelligence and potential of the nation's citizens. Undergraduate and graduate education and training directly cultivate, accelerate, and maximize this scientific potential. According to Layne Scherer, graduate education programs must center student needs, focus on translatable skills that are usable in any career, and encourage students to develop a network of mentors. The importance of mental health in STEM education has been on the periphery for too long and needs dedicated attention. Shirley Malcom noted that the current system of STEM higher education was not designed for the emerging majority, as women and people of color are still excluded because of ethnicity or race. Two-year institutions of higher education, like community colleges, offer significantly more accessible and flexible models of STEM education when compared to four-year ones. Strategies to retain students in higher education programs include active team-based learning, accessible course design, clear expectations for learning and career development, student-organizations that foster belonging, and more. The main takeaway from Shirley Tilghman was that colleges need to think about how to educate students with varying levels of preparation and focus on the “why” students learn science: to apply scientific principles in order to help humanity. She also pointed out that hands-on and authentic research experiences significantly increase the degree-attainment of STEM undergraduate students. Overall takeaways Education is not a private good or a commodity for consumption. Strong and effective models of healthy student-faculty mentor, student-centered education, and targeted initiatives focused on increasing the inclusion of women and people of color exist across the nation. By identifying and articulating the real-world outcomes of our students and their scientific discoveries, we can craft meaningful solutions to better position the nation’s scientific enterprise to allow all students to grow and thrive. The onus lies on the current system of higher education to change, not the students.

REIMAGINING U.S. SCIENCE POLICY TO FOSTER ENVIRONMENTAL AND CLIMATE RESILIENCE

Watch the webinar here

What drew you to attend?

May day job? Astrophysicist. What keeps me up at night? Climate Change. I spend a fair amount of time working with Astronomers for Planet Earth, a climate advocacy group that seeks to provide the climate change movement with an astronomical perspective. When I saw that JSPG, AAAS, and Kavli Foundation were hosting an expert panel discussing how to write about climate change, it seemed as if it was customized tailored for me! This webinar was a great opportunity to get advice on how to write my policy position paper for the JSPG-AAAS competition. The panel was moderated by David Goldston and highlighted four experts in climate policy topics. Takeaways from speakers The panel described how making meaningful climate policy changes is complicated, and that we can take many different roads to achieve the same goal. Amanda Staudt suggested that discussions about the future of climate research are driving it to be more community focused, convergent, and interdisciplinary. David Hart pointed out that, for climate policy, it is important to consider the balances between 1) domestic and international needs and 2) competition and cooperation. These considerations help increase both accountability, to ensure the biggest contributors are being held responsible, and adoptability, to ensure that new climate policy can be easily implemented. Tim Profeta noted that climate change is at its heart an ethical and equitable issue for society. All communities are not affected equally. In particular, lower income and communities of color tend to face the most negative environmental impacts. We must ensure our climate solutions are inclusive, and don’t leave anyone behind. Finally, Gabrielle Dreyfus highlighted the importance of not only thinking about CO2 in regards to global warming, but also other greenhouse gases such as methane and fluorocarbons. These pollutants can trap more heat, increasing global temperatures, and can lead to more atmospheric ozone production which impacts respiratory health. Overall takeaway I took away from this panel both a renewed sense of optimism on addressing the climate crisis and some great advice on how best to discuss it. In particular, this webinar helped me get a better sense of how to effectively write about climate policy. The responsibility of addressing the climate crisis lies with all of us. In order to mitigate the negative aspects of climate change, we must incorporate climate policy into all areas of life - including science policy. If science in the US is to continue to thrive in a carbon constrained future, we must take action now and adopt environmental sustainability as a key aspect of future policy initiatives

RE-EVALUATING SCIENTIFIC MERIT AND REASSESSING WHAT SCIENTIFIC EXCELLENCE MEANS

Watch the webinar here

What drew you to attend?